Many weightlifters quickly dismiss any lower body exercise that isn’t a barbell squat.

But doing so with the belt squat is a big mistake.

The belt squat is a fantastic exercise for building lower body muscle and strength. Not only does it allow you to lift heavy weights through a full range of motion, but it also places little stress on your lower back, making it significantly less fatiguing and easier to recover from than other squat variations.

Why, then, is the belt squat not more popular?

The main reason is that belt squat machines aren’t that common in commercial gyms (though this is changing). Additionally, many people simply don’t know how to perform the belt squat exercise correctly.

The good news is that you don’t need a full belt squat set-up to perform the exercise—there are variations that require less equipment and deliver similar results. What’s more, performing the exercise is straightforward, provided you follow a few simple technique tips.

In this article, you’ll learn how to belt squat with proper form, understand the benefits of the exercise, discover the best alternatives (without a machine), and more.

What Is the Belt Squat?

A belt squat (sometimes called a “hip belt squat” because the belt rests in your hip creases) is a lower body exercise that involves squatting with weights suspended from your waist by a belt.

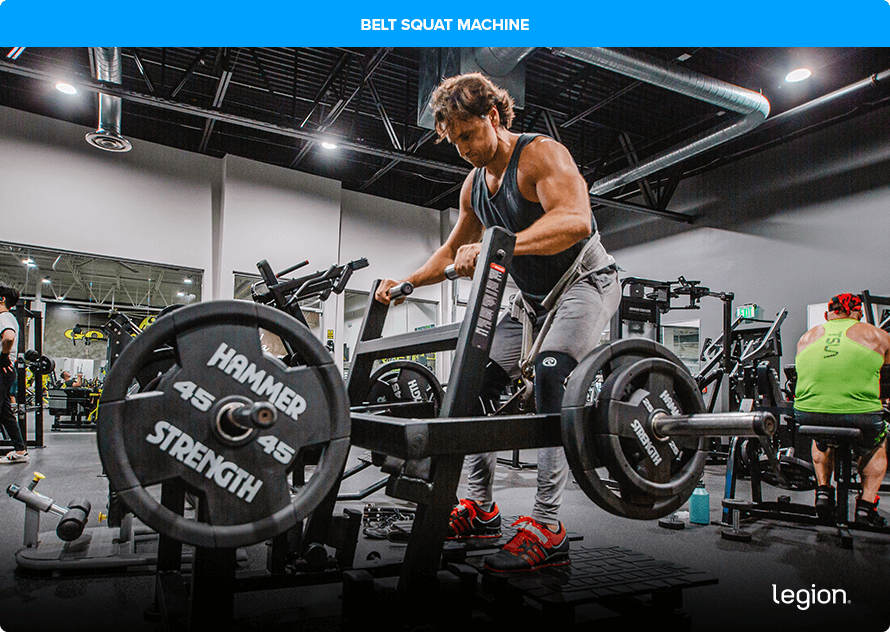

While there are ways to belt squat that require minimal equipment, the most secure and stable method is to use a belt squat machine (often called a “pit shark” belt squat).

A belt squat machine consists of a raised platform where you stand, a pulley or lever system that holds weight, and a belt that wraps around your waist. Once you load the desired weight and secure the belt squat belt around your waist, you hold the machine’s handles and squat.

Here’s how a belt squat machine looks:

How to Belt Squat with Proper Form

To master the hip belt squat, split the exercise into three parts: set up, descend, and squat.

1. Set up

Load the belt squat machine with the desired weight, then stand on the platform facing the machine and loop the belt around your waist.

Squat down just enough to hook the belt to the machine, then position your feet so the belt hangs straight down between your legs, your feet are a little wider than shoulder-width apart, and your toes point slightly outward.

You may need to reposition the belt to ensure it’s comfortable. Most people prefer the belt to be as low as possible on their lower back so that each end of the belt sits in their hip creases.

Grab the machine’s handles with both hands, straighten your legs to support with weight, and pull the handles toward you to release the weight.

2. Descend

Take a deep breath into your stomach, brace your core, and sit down by bending your knees and hips simultaneously. Sit down as far as you comfortably can, ideally until your thighs are parallel to the floor or slightly lower.

3. Squat

Stand up and return to the starting position.

Here’s how belt squat form should look when you put it all together:

Belt Squat: Benefits

Less Lower Back Stress

You don’t support weight with your upper body in the belt squat, so there’s almost no stress on your spine when you perform the exercise correctly. This makes it a safer and more practical alternative to back squats for those with back issues.

High Stimulus, Low Fatigue

The belt squat exercise allows you to train your entire lower body with heavy weights while placing little stress on your spine. As such, it’s typically less fatiguing and easier to recover from than other compound leg exercises, so you can do it more often without wearing yourself out.

Highly Stable

Exercises like back, front, and Bulgarian split squats are fantastic leg exercises, but they require a level of balance and coordination that some people struggle with, especially when new to weightlifting.

The belt squat, on the other hand, is exceptionally stable, particularly when you hold the machine’s handles, so it’s easier to perform with proper form and reduces your risk of injury.

Easy to Learn

Most compound, lower-body exercises require significant time and effort to learn and even longer to master.

The belt squat is different. The set-up and form are straightforward, making it accessible for everyone, even novices.

Ideal for People with Mobility Issues

Because you support the weight with your hips while belt squatting, it removes strain from your upper body and makes deep squatting significantly easier.

This makes the belt squat an excellent option for those with mobility issues that make regular squatting challenging.

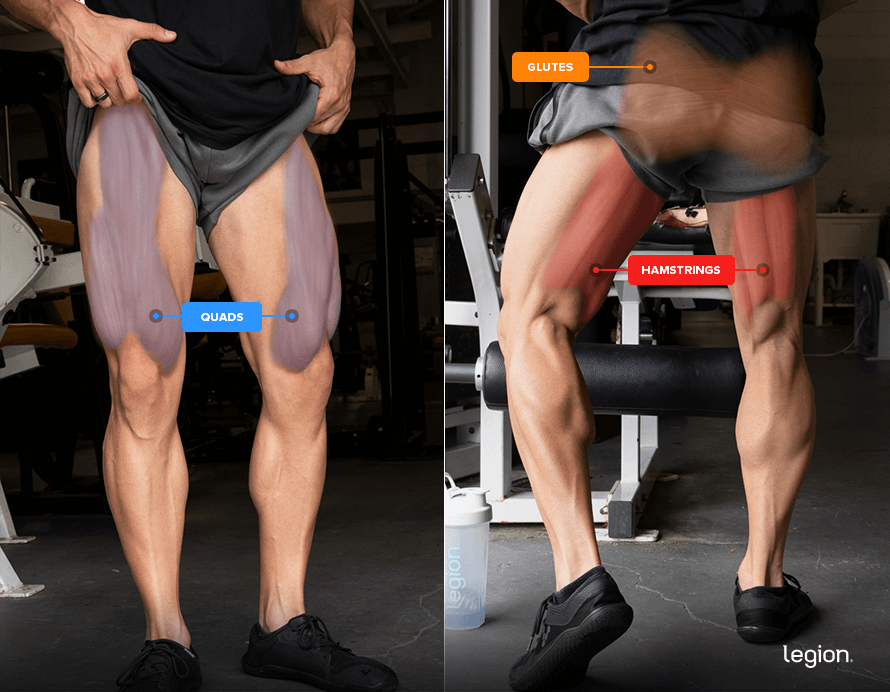

Belt Squats: Muscles Worked

The main muscles worked in the belt squat are:

Here’s how these muscles look on your body:

Do You Need a Belt Squat Machine for Belt Squats?

While a belt squat machine is the most convenient way to perform belt squats, it’s not the only option. You can jerry-rig a belt squat set-up in many ways. Here are the most effective methods:

- Belt Squat Attachment: A belt squat attachment is an adjustable metal arm that connects to one of the uprights on a squat or power rack. They typically have a sleeve in the middle that allows you to load weight plates and a hook at the end where you attach a belt squat belt. Using a belt squat attachment is the best way to replicate a regular belt squat without a dedicated machine.

- Landmine Belt Squat: In the landmine belt squat, you place one end of a barbell in a landmine attachment, load the other end with weights, then wrap a belt squat belt around the weighted end of the barbell and squat. To ensure you can perform the exercise through a full range of motion, it often also helps to stand on weight plates, aerobic steps, or plyo boxes.

- Loading Pin Belt Squat: A loading pin is a rod that holds weight plates. To perform the loading pin belt squat, you load the pin with weights, attach a belt squat belt to the top of the loading pin, stand on two raised surfaces (e.g., weight plates, aerobic steps, or plyo boxes), and squat. Since the loading pin belt squat requires the least space and equipment, it’s a good option for people who train in a home gym.

It’s important to note that whichever belt squat alternative you use will still require a belt.

A regular dip belt can work for landmine and loading pin belt squats. However, if you’re using a belt squat attachment (or machine), a dedicated belt squat belt is preferable. They offer the most comfort, stability, and strength, and they’re more adjustable, so they’re usually the most secure.

The Best Belt Squat Alternatives (Without a Belt Squat Machine)

1. Front Squat

The front squat is a good belt squat alternative because it trains the quads and glutes to a high degree while placing minimal stress on your spine and knees.

2. Leg Press

The leg press is a worthy alternative to the belt squat because it trains your entire lower body without loading your back. It also allows you to lift heavy weights safely and progress regularly, so it’s excellent for gaining muscle and strength.

3. Hack Squat

The hack squat is gentle on your knees and back and trains your leg muscles through a long range of motion, making it fantastic for gaining lower body size and strength.

4. Landmine Belt Squat

The landmine belt squat is a viable option if you don’t have access to a belt squat machine. That said, it requires more balance to prevent the weight from pulling you over, and it has a different “resistance curve” (how the difficulty of an exercise changes throughout the range of motion), which can make the exercise feel awkward for some.

5. Loading Pin Belt Squat

The loading pin belt squat has a similar resistance curve to the regular belt squat, so it’s a workable alternative if you don’t have a belt squat machine. However, setting up the loading pin belt squat can be tricky since you usually have to stand on high surfaces to prevent the weights from hitting the floor at the bottom of each rep.

FAQ #1: Belt Squat vs. Leg Press: Which is better?

The belt squat and leg press are similarly effective lower body exercises that help you gain leg muscle without stressing your lower back.

The main difference is that the hip belt squat is a closed-kinetic chain exercise (an exercise where your hands or feet are fixed) that mimics a more natural movement pattern, so it’s probably superior to the leg press for enhancing athletic performance and it likely trains more stabilizer muscles throughout the body.

Of course, there’s no reason to include just one of these exercises in your program—the best solution for most people is to do both.

A good way to do this is to alternate between the exercises every 8-to-10 weeks of training.

This is how I personally like to organize my training, and it’s similar to the method I advocate in my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

(And if you’d like even more specific advice about what exercises to include in your training program to reach your health and fitness goals, take the Legion Strength Training Quiz, and in less than a minute, you’ll know the perfect strength training program for you. Click here to check it out.)

FAQ #2: Belt Squat vs. Back Squat: Which is better?

Both the belt squat and back squat effectively train the lower body, though the belt squat taxes the glutes and core slightly less than the back squat.

In contrast, the belt squat places less stress on your spine, making it more suitable for those with back injuries. Additionally, it’s easier to learn and perform than the back squat, so it’s an easier starting point for beginners.

Given these similarities and differences, it’s more beneficial to think of the belt squat and back squat as complementary exercises rather than alternatives. Each exercise compensates for the limitations of the other, so incorporating both into your routine is likely the best option.

A good way to do this is to start your leg workout with the back squat, then perform the belt squat later in your workout when supporting muscles like your lower back are bushed, but your legs can still manage another few sets.

FAQ #3: What’s the best belt for belt squats?

Brands like Ironmind and Rogue offer high-quality options. Personally, I use Spud Inc.’s belt squat belt and find it comfortable, durable, and sturdy.

+ Scientific References

- Gulick, Dawn , et al. Comparison of Muscle Activation of Hip Belt Squat and Barbell Back Squat Techniques. June 2015, pp. 23(2):101-108, www.researchgate.net/publication/281391242_Comparison_of_muscle_activation_of_hip_belt_squat_and_barbell_back_squat_techniques, http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/IES-150570.

- Yavuz, Hasan Ulas, et al. “Kinematic and EMG Activities during Front and Back Squat Variations in Maximum Loads.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 33, no. 10, 29 Jan. 2015, pp. 1058–1066, www.growkudos.com/publications/10.1080%25252F02640414.2014.984240/reader, https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.984240.

- Gullett, Jonathan C, et al. “A Biomechanical Comparison of Back and Front Squats in Healthy Trained Individuals.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 23, no. 1, Jan. 2009, pp. 284–292, journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/fulltext/2009/01000/A_Biomechanical_Comparison_of_Back_and_Front.41.aspx, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e31818546bb.

- Schoenfeld, Brad J, and Jozo Grgic. “Effects of Range of Motion on Muscle Development during Resistance Training Interventions: A Systematic Review.” SAGE Open Medicine, vol. 8, no. 8, Jan. 2020, p. 205031212090155, https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312120901559.

- Kubo, Keitaro, et al. “Effects of Squat Training with Different Depths on Lower Limb Muscle Volumes.” European Journal of Applied Physiology, vol. 119, no. 9, 22 June 2019, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-019-04181-y.

- Soriano, Marcos A., et al. “Weightlifting Overhead Pressing Derivatives: A Review of the Literature.” Sports Medicine, vol. 49, no. 6, 28 Mar. 2019, pp. 867–885, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01096-8.

- Kwon, Yoo Jung, et al. “The Effect of Open and Closed Kinetic Chain Exercises on Dynamic Balance Ability of Normal Healthy Adults.” Journal of Physical Therapy Science, vol. 25, no. 6, 2013, pp. 671–674, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3805008/, https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.25.671.

- Kim, Mi-Kyoung, and Kyung-Tae Yoo. “The Effects of Open and Closed Kinetic Chain Exercises on the Static and Dynamic Balance of the Ankle Joints in Young Healthy Women.” Journal of Physical Therapy Science, vol. 29, no. 5, 1 May 2017, pp. 845–850, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5462684/, https://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.29.845.

- Evans, Thomas W., et al. “A Comparison of Muscle Activation between Back Squats and Belt Squats.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, June 2017, p. 1, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000002052. Accessed 9 May 2019.

- Joseph, Lori, et al. “Activity of Trunk and Lower Extremity Musculature: Comparison between Parallel Back Squats and Belt Squats.” Journal of Human Kinetics, vol. 72, no. 1, 31 Mar. 2020, pp. 223–228, https://doi.org/10.2478/hukin-2019-0126. Accessed 25 Apr. 2020.

- Layer, Jacob S., et al. “Kinetic Analysis of Isometric Back Squats and Isometric Belt Squats.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, Sept. 2018, p. 1, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000002854. Accessed 9 May 2019.