Red light therapy is becoming increasingly popular as a fat loss treatment.

According to its champions, it’s a non-invasive procedure that quickly and painlessly “melts” fat, leaving you noticeably leaner in just a handful of sessions.

The best part, they say, is that it’s particularly effective against “stubborn” fat on the belly, buttocks, and thighs, which many people struggle to lose through diet and exercise alone.

Still, many are skeptical of these claims, seeing “laser light lipo” as just another fat loss gimmick that’s unlikely to produce the dramatic results seen in the red light therapy before and after photos found online.

In this article, you’ll learn who’s right, whether getting red light therapy for fat loss is worthwhile, its potential drawbacks, and more.

What Is Red Light Therapy?

Red light therapy, also known as “low-level laser therapy” (LLLT), is a non-invasive treatment that uses low levels of red and near-infrared light.

Hungarian scientist Endre Mester discovered it by accident in 1967, and researchers have since explored it for various therapeutic uses, including weight loss.

According to companies that promote red light therapy for weight loss, the light penetrates the skin with wavelengths that temporarily disrupt cell membranes, shrinking fat cells and causing the body to eliminate them.

During an infrared fat loss session, a trained professional applies the laser to the treatment area for 10-to-40 minutes. Since red light therapy is non-thermal (doesn’t generate heat) and nonablative (doesn’t damage the skin), you can go about your day as normal immediately afterward.

While recommendations vary among “red light lipo” providers, most suggest at least five sessions to see results, with more sessions needed for a significant change in body fat levels. Providers often also encourage patients to maintain healthy lifestyle habits, such as following a calorie-controlled diet and exercise routine, alongside the LLLT treatment.

Does Red Light Therapy for Weight Loss Actually Work?

Despite countless positive testimonials from people who have received red light therapy for weight loss, most experts remain skeptical about its effectiveness.

Their skepticism likely stems from the controversial research in this area. While results often appear promising, they’re usually less compelling when examined more closely.

For example, one study many point to as “proof” of red light therapy’s fat-burning effects was published in The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology. In this study, participants received either three 20-minute LLLT sessions or “sham” (fake) treatments per week for two weeks.

After six treatments, the LLLT group reduced their upper arm circumference by an average of 1.5 inches, while the sham group saw little change. The LLLT group also felt more satisfied with their results.

However, the study had several limitations:

- Only 40 people participated.

- The researchers measured fat loss with a tape measure, which is generally unreliable.

- They relied on subjective measures like satisfaction and perceived improvement, which are prone to bias.

- They didn’t monitor the participants’ diets and exercise habits

- An LLLT treatment company funded the study, increasing the likelihood that bias colored the data.

Another study published in Lasers in Surgery and Medicine found that participants receiving two weekly LLLT sessions for six weeks lost an average of 2.2 pounds, reduced their waist circumference by 2 inches, and reported improved quality of life and body satisfaction.

These results would be impressive if not for two issues:

- The researchers advised the participants on how to alter their lifestyle to promote fat loss but didn’t monitor their diet and exercise regimens.

- There was no control group.

Therefore, the participants might have lost weight because they ate less and exercised more, not because of LLLT. But without a control group, we can’t be sure.

Similar methodological flaws affect most research on red light therapy and fat loss.

For instance, a study by George Washington University found that two weeks of LLLT reduced people’s waist by 1.1 inches, hips by 0.8 inches, and thighs by 1.2 inches. But this study wasn’t randomized, didn’t have a control group, had participants take a stack of supplements (some of which may promote fat loss), and used a tape measure to measure fat loss.

Another study published in the Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology found that LLLT reduced people’s waist, hip, thigh, and upper abdomen circumference, but its funding came from a LLLT provider.

The scientific literature contains many more examples of LLLT producing significant weight-loss results. The problem is none of them hold up under scrutiny. Until stronger evidence becomes available, tempering your expectations of red light therapy as a fat loss treatment is sensible.

Downsides of Red Light Therapy

Unclear Long-Term Effects

Scientists are still studying red light therapy’s long-term safety and effectiveness for fat loss. Until more research explores its potential side effects and benefits over time, undergoing this treatment carries some risks.

Inconsistent Results

Results from red light therapy can vary widely. Most studies have involved people with a BMI of 25-to-30. If your BMI is higher or lower than this, you may not get comparable results.

High Cost

Red light therapy can be expensive, especially since most providers recommend having multiple sessions before you see results.

To avoid this issue, some people invest in at-home light therapy devices. However, there’s no guarantee that home devices are as effective as those used by professional LLLT treatment centers and may not deliver similar (or any) results.

Time-Consuming

Receiving daily treatments of red light therapy is time-consuming and impractical.

Doing three strength training workouts per week would likely take up less time and have a more profound and lasting impact on fat loss.

Results May Be Temporary

Without changing your lifestyle, you’ll likely regain any fat you lose through red light therapy when you stop receiving treatments.

A Better Way To Lose Fat (Without Red Light Therapy)

You don’t need new-fangled fat-loss treatments to get the body you want. In fact, improving your body composition is simpler than most people realize. It mostly comes down to:

- Eating the right number of calories for your goals

- Consuming plenty of protein

- Lifting weights regularly.

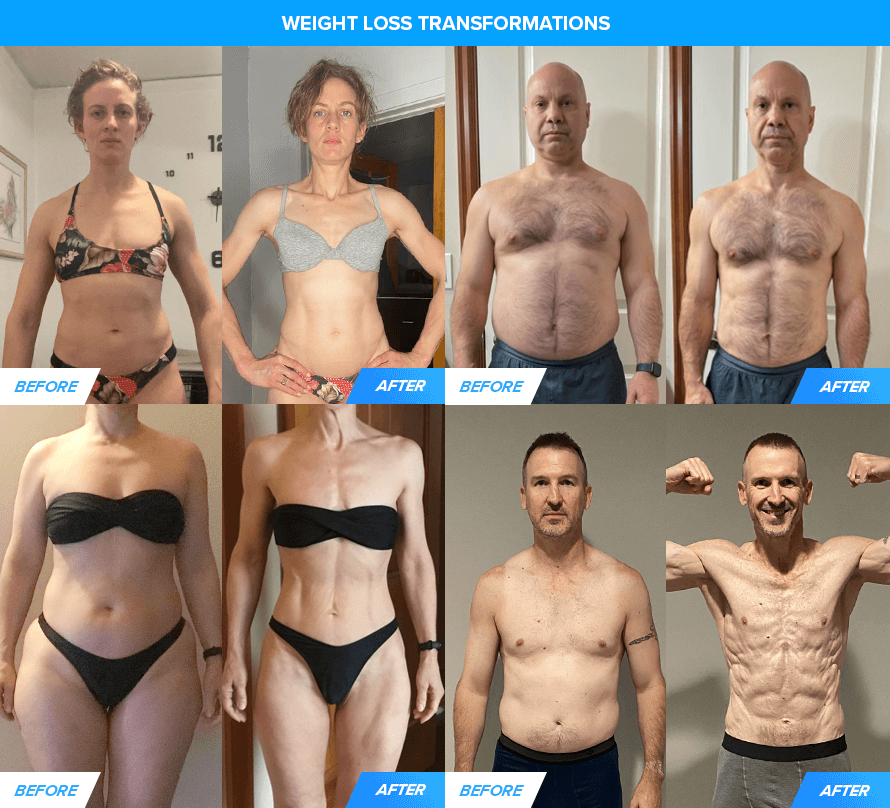

This is the exact protocol these people followed on Legion’s body transformation coaching service, and look at how their bodies changed:

If you want to achieve similar results, here’s what you need to do:

Eat the right number of calories.

Studies show that eating 20-to-25% fewer calories than you burn every day will help you lose fat lickety-split without losing muscle or wrestling with excessive hunger, lethargy, and the other hobgoblins of low-calorie dieting.

To learn more about how many calories you should eat to lose fat, check out the Legion Calorie Calculator here.

Eat enough protein.

High-protein dieting beats low-protein dieting in every way, especially when you’re dieting to lose fat.

Aim for 1-to-1.2 grams of protein per pound of body weight daily.

And if you’re very overweight (25%+ body fat in men and 30%+ in women), reduce this to around 40% of your total daily calories.

Lift weights.

To maximize the fat-burning effects of strength training, do the following:

Conclusion

While red light therapy is gaining popularity for fat loss, the evidence supporting its effectiveness is pretty weak. Most studies showing its benefits have methodological flaws, making the results difficult to trust.

What’s more, red light therapy is still a relatively new treatment, so its long-term safety and effectiveness remain unclear. It can also be expensive, time-consuming, and may only offer temporary results, making it even less promising.

A more reliable and sustainable approach to improving your body composition involves eating a calorie-controlled, high-protein diet and regular exercise, particularly strength training.

To learn more about how to eat and train to lose fat and gain muscle, check out my fitness books for men and women, Bigger Leaner Stronger and Thinner Leaner Stronger.

+ Scientific References

- Nestor, Mark S., et al. “Effect of 635nm Low-Level Laser Therapy on Upper Arm Circumference Reduction: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Sham-Controlled Trial.” The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology, vol. 5, no. 2, 1 Feb. 2012, pp. 42–48, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22468172/. Accessed 3 July 2024.

- Croghan, Ivana T., et al. “Low-Level Laser Therapy for Weight Reduction: A Randomized Pilot Study.” Lasers in Medical Science, vol. 35, no. 3, 1 Apr. 2020, pp. 663–675, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31473867/, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-019-02867-5. Accessed 16 Feb. 2022.

- McRae, Elizabeth, and Jaime Boris. “Independent Evaluation of Low-Level Laser Therapy at 635 Nm for Non-Invasive Body Contouring of the Waist, Hips, and Thighs.” Lasers in Surgery and Medicine, vol. 45, no. 1, Jan. 2013, pp. 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.22113. Accessed 15 Jan. 2022.

- Thornfeldt, Carl R., et al. “A Six-Week Low-Level Laser Therapy Protocol Is Effective for Reducing Waist, Hip, Thigh, and Upper Abdomen Circumference.” The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology, vol. 9, no. 6, 1 June 2016, pp. 31–35, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4928454/. Accessed 3 July 2024.

- Huovinen, Heikki T., et al. “Body Composition and Power Performance Improved after Weight Reduction in Male Athletes without Hampering Hormonal Balance.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 29, no. 1, Jan. 2015, pp. 29–36, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0000000000000619.

- Farinatti, Paulo TV, and Antonio G Castinheiras Neto. “The Effect of Between-Set Rest Intervals on the Oxygen Uptake during and after Resistance Exercise Sessions Performed with Large- and Small-Muscle Mass.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 25, no. 11, Nov. 2011, pp. 3181–3190, https://doi.org/10.1519/jsc.0b013e318212e415.

- MARX, JAMES O., et al. “Low-Volume Circuit versus High-Volume Periodized Resistance Training in Women.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, Apr. 2001, pp. 635–643, https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200104000-00019.